Back in august of 2016, the finals of the 2016 DJI Developper Challenge were held at the Griffiss International Airport, one of only 6 FAA approved UAS testing sites at the time. Our team, previously known as SaveApril and then as MRASL (the name of our lab) was part of the 10 finalists picked from an initial batch of 130 development proposals submitted to the competition.

Contest Rules and Objectives

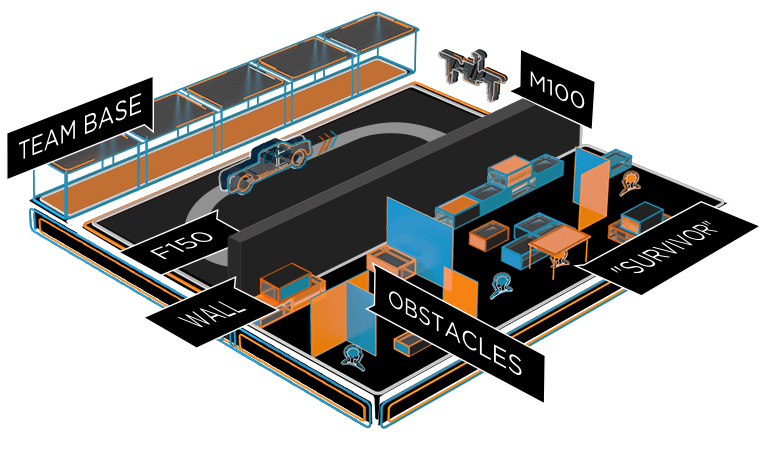

The basic idea behind the challenge was a mock humanitarian mission where a quadcopter had to take off from a moving pickup truck, enter a disaster area to find survivors and come back and land on the same moving pickup truck. After speaking with the organizers though, it was admitted to us that they were mostly interested in seeing the moving landing happen.

Selection rounds

The challenge would be split into 3 selection rounds followed by the finals in august. Each round had a certain number of minimal deliverables and would slowly narrow down the contestants, thus we had:

- Development plan

- Deliverable: feasibility analysis and team member biographies. Basically something to show that you could actually do the mission.

- Result: 25 teams (including us) are selected to receive mandatory DJI equipment (M100, Manifold, X3 camera)

- Initial vision processing

- Deliverable: Progress report, detection and positioning of an AprilTag (probaly left intentionally vague)

- Result: Team MRASL rejected at this round but is invited to submit to round 3 anyways for a chance at redemption. MRASL loses spare parts support from DJI and does not receive a secondary flight battery.

- Demonstration of mobile landing and obstacle avoidance

- Deliverable: Video demonstrations of the main difficulties of the challenge.

- Result: MRASL revived back into the competition and makes it to the top 10!

- Finals

- Top 10 teams gather at Griffis International airport to attempt a full mission.

- Result: Read on to find out!

Mission Challenges

1. Takeoff

The first challenge was to take off from the Ford F150 truck while it was driving at a certain speed. The reason DJI considered this a challenge itself was probably because it was liked to other fluff requirements such as having the mission started using the Ford API. Surprisingly enough, some teams failed this challenge (including us on practice day).

2. Survivor search

Next, the MAV has to enter the search area and find survivors represented by AprilTags 5 x 5 centimeters large. I believe this was intentional to force teams to actually enter the area and do obstacle avoidance in order to get close enough to id the tags. 5 survivors would be placed on certain walls, inside a small house and on the ground.

3. Moving Landing

To end the mission, the MAV has to navigate out of the search area back to a Ford F150 truck and land on it. Additional points are awarded if the truck is moving. A very important thing to note here is that the scoring system was such that the moving landing itself was worth 9 extra points. This meant that if you knew no one could find all the survivors and do the moving landing, you could limit your mission to only performing the moving landing and not bother looking for survivors and risking getting stuck or crashing in the search area.

4. Side Challenges

In addition to all of the above, we were strongly encouraged (some parts were mandatory) to develop a mobile application which could communicate with the car and allow operators to start the mission.

What happened

The Beginning

Our team was initially composed of 1 Ph.D. student, 3 M.Sc. students and 1 M.Sc. graduate. Out of this initial team only two of us, myself included, had any kind of experience with practical aerial robotics and ROS. In fact, Alex and I had successfully competed twice at the International Aerial Robotics Competition (IARC). With this in mind, we knew there would be a steep learning curve for our team to surmount. Nonetheless, our initial development plan had a positive outlook on the feasibility of solving this challenge, it wouldn’t be easy but all the theory had already been developed by other researchers before us. We knew we would need a Kalman Filter to estimate the position of the car and some kind of SLAM and path planning system to be able to navigate the disaster zone.

In the days surrounding the announcement of the 25 teams being picked to start the competition, we kept refreshing the website and checking the developer forum for news. As the comments in the thread came in, I kept googling the names in hopes of better understanding who our competition was.

When the results came out that we were picked (under the name SaveApril to hide our identity) we were ecstatic! When we started research in to our fellow competitors we were terrified.[^1] Big names were present on the list such as TU Graz, Georgia Tech, Stanford (as team Cardinal S.A.R.), University of Hong Kong and Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST).

Round 2 - Disapointing Results

After our development plan was accepted we started working on the moving landing simulation in Gazebo as well as some computer vision work while we waited for the equipment to arrive. Fortunately for us, we already had access to an M100 and a DJI Guidance module thanks to winning the top performer award at the 2015 IARC.

The second round submission also came at a difficult moment close to the end of semester so I had attempted to take the opportunity of using one of my class projects to work on the competition but for the most part, we didn’t put as much work into the competition as we should have.

Initial testing using the Guidance video feeds showed abysmal AprilTag detection results. Since the Guidance cameras are low resolution, the tags could only be detected at a distance of about 1 meter. I set to work on creating a convolutional neural network to hopefully detect tags at a greater range to help our quad explore the search area in an informed way. This turned out to be a complete flop and I had only managed to increase the range by at most 0.2 meters. At least I got a good grade on that project.

In parallel we started work on a simulation of the landing procedure using Gazebo and the RotorS simulator which also included getting an accurate 3D model of a Ford F150 pickup truck with suspensions and Ackerman steering working. The model is now open source and available on Github.

As the deadline got closer and we finally received our equipment, we scrambled to write a simple PID controller which would point the X3 gimbal camera towards an AprilTag. This meant we would meet the strict minimum of our interpretation of what had to be submitted for the next round.

Unfortunately for us, our submission was a complete flop and we weren’t picked in the top 15 teams to move on to round 3. Our mistake was thinking that our simulation work had been enough to convince DJI we were on the right track to do the landing. However, the competition judges heavily favored teams who had immediate real world results rather than teams showing more planning and in depth simulation. I’ve assembled a playlist on Youtube showing all the submission videos I could find. A general theme for round 2 was that most teams had real flight tests while we did not; DJI’s decision was entirely warranted.

However, DJI still encouraged teams who weren’t in the top 15 to keep going and submit a report to the 3rd round. This would mean we would no longer be eligible to DJI’s equipment replacement policy and we would have to fund things out of our own pocket (or borrowing things from the lab and some friends).

To be continued…