Round 3 - Scrambling Back on Track

A recurring theme for round 3 was that we kept wasting time on things that would end up not being used. This was mostly my fault in terms of being an effective team captain. This weakness stemmed from not having a clear idea of the most effective path towards accomplishing our goals. We were experimenting and entirely unsure of the most effective way of accomplishing things.

Things started off with us scrambling to get up to speed with other teams. We quickly got familiar with the provided SDK and started doing simple flight tests where we would follow a tag pulled by some rope without even having a Kalman Filter. The start of round 3 also coincided with the beginning of the summer semester where three of us were taking the Navigation Systems class. A very demanding class which we would also end up using as an excuse to write an early version of the Kalman filter for the estimation of the position of the landing pad.

This is where we made a significant mistake in project planning. Things got set up in a way that we were almost 5 people working on the landing algorithm. What little time I had left on the side I would dedicate to doing anything computer vision related including some work on the X3 driver, AprilTag detection and a custom version of the DJI Guidance driver. To this day, the new driver I wrote is still incomplete but it is available on Github.

Landing

At first we did some small scale testing where we would fly indoors and take off just a few meters away from the an AprilTag. With this setup we iterated through a few ideas including a Fuzzy controller and a PID controller. It took a long time before actually setting ourselves on one method and correctly developing the controller for it. Again, we kept questioning ourselves and going back and forth through things still unsure about the most optimal method of accomplishing our goals. This was nice on a small scale, but we needed to start thinking big. Think - approach from a few hundred meters away - big.

Proportional Navigation - GPS Based Approach

Early on, our professor had suggested using Proportional Navigation (PN) for the approach maneuver. Usually a PN controller is used in air target missiles to steer it and keep it on a collision course with a target. Note that the PN only controls the rotation of the velocity vector. I suppose this is because missiles don’t usually control their thrust (or can’t) and simply burn their fuel at a constant rate. In any case, we figured if we ended up creating the drone equivalent of a ballistic missile crashing into a Ford F150 we would win the $100K since DJI never specified we had to land on the truck in one piece. Right?

The first step in implementing our landing estimator in conjunction with the PN approach method was getting a vague idea of where the car was. If we could get within a few meters we knew the X3 would eventually pick up on the large AprilTag. I believe it’s around this time that Alex introduced the idea of having a Mobile Phone which became a central aspect of our landing method.

An interesting fact about the competition was that Ford wanted to promote it’s AppLink API. While we found out the API could provide rich information we could have used to estimate the truck’s trajectory including steering wheel angle, tire pressure, wheel RPM and GPS data, we were told by the Ford representative that we wouldn’t be getting access to that information.I set out to find another way to get to the truck without having to actually fly through the predetermined trajectory to find the truck.

We next examined the DJI remote controller. Though it looks plain white, it’s price tag of upwards of 500 USD is a hint at what kind of technology is packed in there. It can actually provide GPS data to a mobile phone attached to it. After some quick testing I found out that the new data event was triggered only when significant change in the RC’s position happened. Even when running around, we found out the callback was only triggering at an inconsistent rate with delays of a few seconds. This was far too low for us to get things working.

At this point, things naturally led us to think Hey, we have this mandatory mobile app to write, why don’t we write it for a smartphone that has GPS capabilities? Thus, we discovered that an Android cellphone can provide GPS data at a confident 1Hz, which was more than anything we had at the time. We figured if DJI made us use a tablet without GPS on competition day, we would just say we didn’t have the .APK to transfer the app and that it was already installed on our GPS capable phones. And while we were at it, we could also use the phone’s IMU as a measure of the acceleration of the car. Remember, competitions aren’t about playing the spirit of the rules, they’re about playing the rules themselves :joy::laughing:.

The next question we had to ask was: How do we get this data to the MAV for the landing estimator? It came down to three options:

- Add a 3G/4G chip to the MAV get the data through the Internet.

- Though this would add weight and more power consumption, it would make sense if the competition area ended up being very large. At the time we only had drawings of what the competition would look like, but no clear idea of how big the landing track was or how far it would be from the search area. It would also add non-negligible time offsets to the data which would be a pretty bad idea.

- Use DJI’s Data Transparent Transmission which goes through the remote controller.

- It’s unclear (it being proprietary and all) how this works but our theory is that it piggy backs on the the DJI Lightbridge video feed to create a low bandwidth data channel between the M100 and the RC. We didn’t like this idea because it would mean that during testing the remote would need to be where the drone would land. But we needed our safety operator on the side so that he could observe what was happening.

- Use a WiFi network.

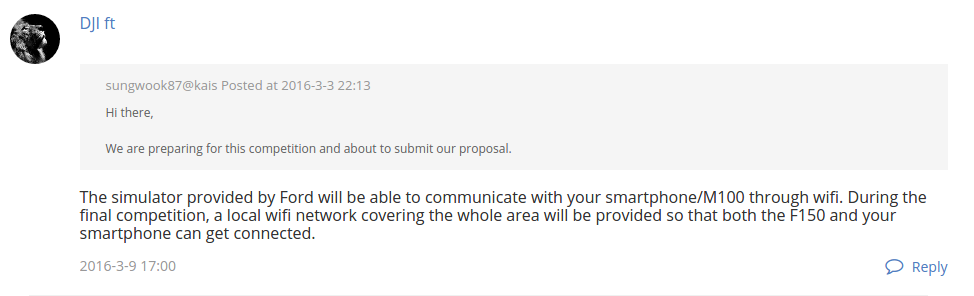

- It turned out that we weren’t the only team wondering about this and forturnately enough for us DJI responded to him by saing there would be Wifi everywhere.

Thus, we set out to develop our system with a Wifi back-end to provide the M100 with the F150’s position. Little did we know this would eventually be the source of many headaches and a contributing factor in our eventual loss. This is such an important point that I think I should put it in big quote letters.

Little did we know [Wifi] would eventually be the source of many headaches and a contributing factor in our eventual loss.

Getting Close - Why It Is Useful to Understand All Aspects of Your System

With GPS data incorporated, it wasn’t long before we had an estimator allowing us to track a wooden platform onto which we would lay a mobile phone.

It was then, that the experience Alex and I had previously acquired really shined through and allowed us to make a clear cut decision that would put us in front of many teams as far as we could tell from the 3rd round submissions.

We understood that the DJI Guidance worked in a similar way to the px4flow (this is a gross simplification but the end result is the same) where a camera pointed to the ground tracks the movement of features to compute a visual estimate of the M100’s velocity. What would happen then if the quadrotor was on top of a moving platform? The answer is quite obviously that the velocity estimate becomes incorrect and the quadrotor would think it is moving when it is not. You can do the test yourself, we did, hover your M100 or any of DJI’s products equipped with optical flow on top of a platform. Then slowly move that platform and you will see the your quadrotor move with the platform.

The implication of this was that any team using velocity control to land the M100 on the truck was bound to fail unless they got very lucky or tried to accelerate onto the truck from behind. It was clear however that you wouldn’t be able to accurately track the truck from the top. A notable example of this was team HKU.

To mitigate this problem we wrote our PN and PID controllers to issue acceleration instead of velocity commands. Our acceleration commands are then translated into attitude commands which we send to the M100. A full derivation of the equations required to do this translation is available in our paper.

Visual Target Acquisition - Thanks Edwin Olson!

During the approach phase we use the estimated landing pad position to point the X3 camera towards where we think the vehicle is located. This means that as we get closer to the landing pad, we are pretty much guaranteed to eventually see the landing pad unless the error between the M100’s GPS and the mobile phone is large enough such that the camera will always point right next to the truck which is unlikely. One thing we came to eventually realize was that as the M100 lowered itself towards the landing pad, the X3 would fail to detect the large AprilTag.

AprilTags are a sort of 2D bar code which can only be read one way. When you figure out which way to correctly read the code, you can then extract the four corners of the tag and solve a PnP problem to recover the pose of the tag w.r.t. to the camera or vice-versa. Recall that the landing pad is equipped with one large AprilTag and smaller AprilTags arranged in a cross pattern.

It was clear that DJI meant for the cross pattern to be part of a multi-scale fiducial that teams could use once they got close. In fact, I did write a cross pattern detector performing solving the PnP problem using the center of each tag. The detector was even part of a Kalman Filter which we submitted as our semester project for our summer class on Navigation Systems.

In any case, the problem wasn’t only that the X3 couldn’t see things up close but it was also about how the X3’s gimbal doesn’t provide accurate attitude measurements (at least, not for our use). In fact, it was mentioned on Github that it was difficult to accurately control the X3’s yaw. The problem stems from the fact that the gimbal provides it’s data in the world frame instead of the M100 body frame. In a way this makes sense, to stabilize a camera, you want it to be stabilized w.r.t. to the world’s gravity. In practice this is troublesome if you want to point the gimbal forwards, to the front of the body frame. Moreover, it was also a problem on the estimator side. As @Groundmelon mentioned, subtracting the attitude of the gimbal to the attitude of the drone to find the transform between the gimbal and the body frame doesn’t have a lot of precision. This introduces errors into the estimation of the landing pad’s position w.r.t. the M100. To further compound our problems, we would sometimes fall into a gimbal lock situation when the X3 was pitched straight down.

To alleviate these problems we introduced the use of a camera rigidly attached to the bottom of the M100. We couldn’t use the Guidance camera because its field of view was too small and its resolution is too low. Hence, we added a MatrixVision BlueFOX2 camera to our M100 with an ultra wide angle lens. With this new setup we had AprilTag detection right up until the very last moments of the landing maneuver. This was a game changer and a strong contender to the mobile phone’s IMU as the most impactful feature. This also meant that the AprilTag cross detector was developped for nothing and more work was done for nothing :sob:.

With less than two weeks left to our submission, multiple successful landings were performed on a wooden platform pulled by a poor soul in our team (we took turns). It was clear we had to go out and perform the landing on a car at 30 km/h. At the time, we were convinced every other team was going to be able to do it and that meant we had to go all in or it would be the end of it. I mean, if we were able to get this close, the other teams must have been able to do it.

Thus, team MRASL set out to an undisclosed location on a road in an abandoned industrial development project to show the world we could do it.

SLAM and Obstacle Avoidance

On the navigation side things weren’t going well and what little work we were able to do was for the most part going no where, echoing my previous failure with my neural network. At the time, the thinking was that we absolutely needed a SLAM system to be able to navigate the arena in a consistent way and to make sure we explore everything.

Although the DJI Guidance claims an “effective sensor range” of 0.2 to 20.0 meters range, in practice the point cloud is only useful up to a few meters, after that the cloud is much too noisy. I believe that later on, with aggressive speckle filtering we were using the point clouds at up to 7 meters, which wasn’t too bad if you only cared about knowing if an obstacle was present or not (probably a bad idea to use the Guidance for SFM). For the time being though, we decided to mount a Hokuyo lidar onto the M100 to be able to have 20 meter scans of the search area.

At first we had attempted to run Real-Time Appearance-Based Mapping (rtabmap) onboard, this would allow us to have a consistent map of the area with a full octomap representation for navigating. The problem however was that it was very demanding in terms of computing power and we felt like the included visual odometry (VO) algorithm seemed too imprecise for our needs. I came to the realization that maybe a full SLAM system wasn’t actually required since the Guidance already gave good VO data and the M100 seemed to have an excellent navigation system. It’s at this time that we simply started inserting point clouds directly into an octomap using only the onboard odometry as a source of positioning.

Time was running out and what had been attempted in terms of obstacle avoidance until now hadn’t worked. In particular, one of our team members had attempted to get the optical flow based obstacle avoidance example working without success. We thought we needed some kind of 3D path planning algorithm in case the disaster area ended up being highly cluttered and the MAV needed to navigate under and over obstacles. The general thinking was that if we could simply cover the search area in a lawn mower pattern. As the MAV navigates that high level trajectory, an obstacle avoidance path planner could plan intermediate waypoints to safely execute the lawn mower trajectory.

In an incredibly desperate last-ditch effort, one week before our 3rd round submission was due, we started working on replicating the work of Alessio Tonioni who used MoveIt! to get a virtual quadcopter to navigate some paths. After a lot of tinkering, swearing and takeout food, we got things working merely hours before the report was due. The day we got things working, we knew we wouldn’t be able work outside since we were setting ourselves up for working through the night. Because of this, we cheated a little bit and actually used our Vicon setup as odometry. In practice, the M100’s odometry was precise enough to execute the trajectories, so we figured, having the Vicon odometry instead wasn’t a huge advantage.

The general idea for using MoveIt! in our case was to model the MAV as a single free floating joint. The MAV is modeled as having the footprint of a sphere. At first we modeled it as a rectangular prism, however sometimes MoveIt! would attempt to roll our MAV 90 degrees to get between two obstacles, modeling the MAV as a sphere meant that MoveIt! didn’t gain anything from changing the attitude to avoid obstacles. We couldn’t get MoveIt!’s replanning feature working so we ended up calling the planner at fixed intervals so that it would take into account new obstacles as they were discovered.

Our Damn Good Video Submission

So all of this culminated in creating this incredibly nice video demonstrating static landing, moving landing at 10, 20 and 30 km/h. With a nice little segment in the end of our M100 navigating a mini maze. We submitted everything with only a few minutes remaining at 3 AM. After all the hard work, all the crashes and all the uncertainty and doubt we had finally done it.

To be continued …