Note: I am now writing thing almost a year later so some of the finer details have been lost or are a bit fuzzy. In fact, this post will probably be much shorter than the previous ones.

End of July not long after we submitted our 3rd round report, DJI released the names of the teams selected to participate in the final round at Griffis International airport. We were esctatic to know our hard work had paid off and we were back in the finals as a revival team. Moreover, we frantically looked all over youtube trying to find other teams and realized no one else had been able to perform a moving landing as good as ours. Most teams could at best follow a moving tag or land on a very slow platform. Our guess is that many teams didn’t fully understand the implication of having the DJI Guidance attached to the M100 platform. Since the Guidance give pose estimation to the M100 using downwards facing visual-inertial odometry, once the drone is on top of the moving platform, the M100’s velocity estimation becomes wrong. Thus, if you attempt to land on the car using velocity commands, the M100 is unable to follow your commands! Unfortunately, we couldn’t find anything from certain key teams such as Autero, Cardinal SAR (from Stanford) and Graz Griffins (from TU Graz).

Most teams however had made much progress in the search and rescue aspect of the competition and had good obstacle avoidance systems that seemed much simpler than our MoveIt! based system.

This is where we made a key judgement call that ultimately put a lot of strain on the team. We decided that even though to our knowledge we had the best and maybe only working moving landing, all teams would eventually be able to catch up to us in time for finals. That meant we had to invest more time the search and rescue operation and still keep pushing the landing to make it robust. In retrospect, only Autero and another team had or were close to having a landing, that meant that we could have won by completely dropping the search and rescue mission and focusing everyone on the landing. However, with the information we had it was be right call.

Moving away from MoveIt!

Our first order of business was to find a better alternative to MoveIt!. We had multiple problems with MoveIt! having to do with how ressource costly it is, how most of our environment could be simplified to 2D and how it didn’t fix our problem of needing an exploration algorithm. After testing a few things including ETH-ASL’s Next Best View Planner, we settled on TU Darmstadt’s team Hector’s exploration planner. Since an exploration planner tries to get close to unknown space by moving through free space, it’s also an obstacle avoidance module! You can see it working in the following video

We had two major problems with our approach, the first was that we would often get noise or speckles inserted into our obstacle map. This was due in part to having our test area up on a hill. This meant that late in the day, our stereo cameras would look directly at the sun and fasely resolve as an obstacles. No matter how much filtering we applied, we couldn’t get rid of those speckles. We had to resolve to some clearing maneuvers if ever the robot got stuck including doing a 360 on itself and simply clearing a 1m radius around it in the occupation map.

The second major problem was defining the boundaries for exploration so our drone didn’t go somewhere not in the competition arena. The competitions in which team Hector participate are SAR scenarions in closed environments with walls around it. Unfortunately for us, we had to find some way of inserting a virtual fence for our robot to stay in. To do this at each iteration, we drew virtual walls back into our occupancy grid before the planning step and after the cloud insertion step. Not ideal, probably slow, but it worked (kind of).

Comms problems

One problem we spent a good amount of time attempting to solve was the problem of the communication between the drone and the vehicle. As stated in my previous post, we used the mobile phone’s IMU as a measure of acceleration of the vehicle to better predict the speed in our Kalman filter. This data was sent to our drone through Wifi which we had assumed would be present at the arena on competition day as it was stated in the DJI forums. However, as competition day got closer, we learned that the Wifi network was for DJI’s internal use only (video streaming) and that we had to notify them if we were to bring our own communication equipment. Moreover, we couldn’t understand how we were supposed to send the images of the detected survivors back to the car if we didn’t have Wifi. Cue panic.

We went through quite a few scenarios including mounting multiple TP-Link Pharos wireless access points on the car at different angles to make sure the M100 would be able to connect at all times. The ranges we had to take into account were pretty large and forced us to choose long range wifi equipment. We settled on a very large and very high gain Ubiquity airMAX Omni antenna and a Unifi access point. On the M100 side we stuck to our old setup using regular antennas with an Intel wifi chip. If you’re reading this to reproduce our setup, don’t. What we hadn’t understood is that you can’t just have one side be high powered and keep communications up. For this to work, you need to have both the access point and the client use high quality equipment. If I had to redo it, I would probably put Bullet M’s on the M100.

Final stretch and systems integration

As the competition got closer, the need to fufill the mandatory requirements to have an Android app show our survivor detections became more urgent. We recruited Gabriel into our team for the app. Most of it went pretty smooth except for the fact that a few months earlier, DJI had broken their Mobile SDK and it wasn’t able to correctly read the video stream coming from the remote controller for more than a few seconds. The only reason we were able to discover this is that we had see teams be able to build an app as soon as round 1. So we reverted the SDK to the months of february/march and everything started working again.

Although we were tired and way overworked, things were looking good and all the pieces started fitting together. Our state machine was functional, we had used the entire parking lot to try a full mission end to end. We weren’t sure we would be able to find all the survivors but it didn’t matter that much because we knew our landing would give us a huge advantage in terms of points.

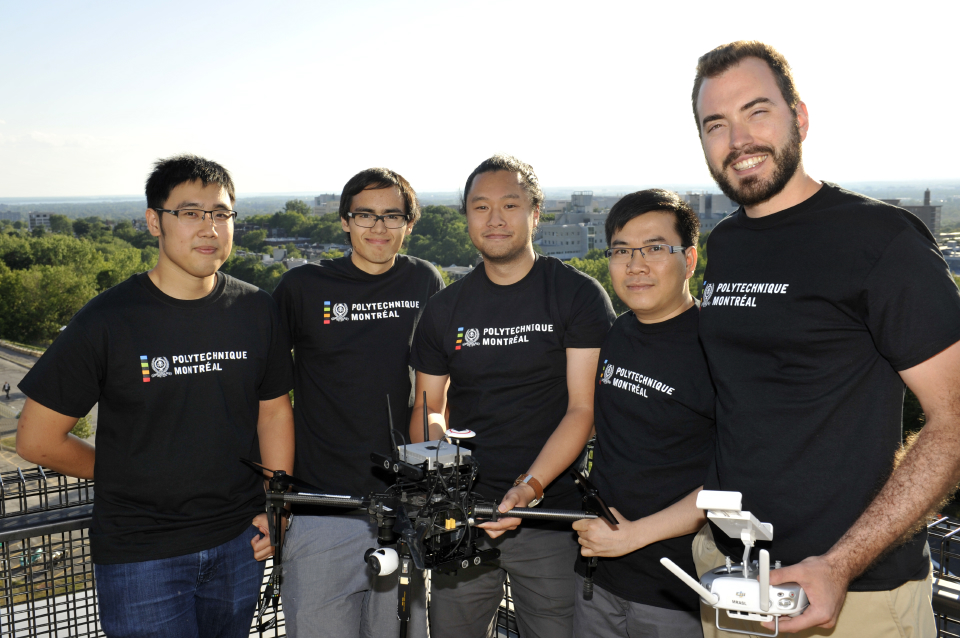

As a side note, our school started becoming interested in what we were doing and had a little marketing campaign going on. We appeared on the tv show RDI Matin Weekend, the radio show RDI 15-18 and eventually Planète Techno on the Explora channel.

To be continued…