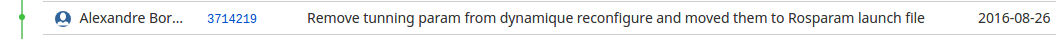

In the time after the competition Alex figured out what had gone wrong. On august 26th 2016, just two days before the competition, a commit had gone in to refactor some flight parameters and simplify things.

Seems like a simple enough change right? Move away from ROS’ dynamic reconfigure infrastructure and simply use parameters written in launch files. The dynamic reconfigure was important for field trials where we were empirically tuning flight parameters and we needed a way of quickly changing things on the fly. Let’s go through the changes introduced by this commit.

So the first change we can see that the parameters are removed from the parameter generation file and put into the launch file. Some parameters are outright removed and some values are changed but nothing too out of the ordinary. Yaw parameters were removed (but reintroduced farther down) and the flight_level_low was reduced from 3.75m to 3.5m.

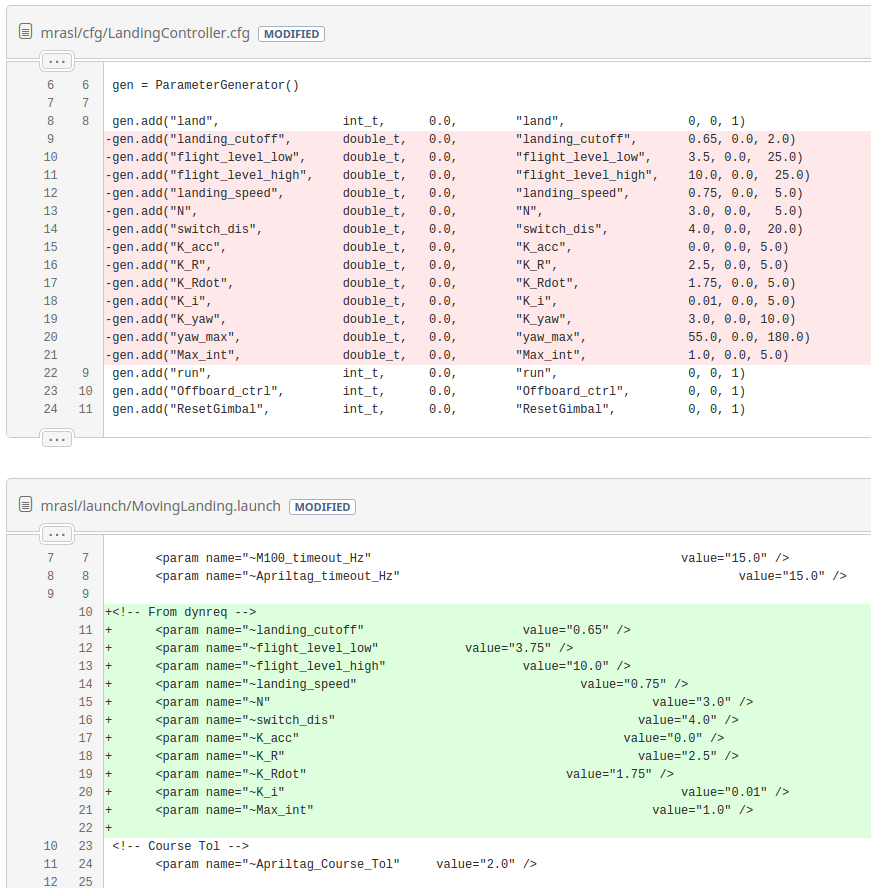

Next, we had changes in the moving landing node itself. The callback is simplified to remove parameters which are no longer in the .cfg file and lines are added to fetch them directly in the parameter server. Can you spot the mistake? To fully grasp the mistake we need a bit of background information on dynamic reconfigure. As Jack O’Quin explains:

When you register your [dynamic reconfigure] callback, it gets invoked immediately with the values currently defined in the parameter server and a level of

0xffffffff. Those initial values will include anything set in your launch file. You don’t need to read the parameters yourself usinggetParam().

If you look at the configure callback of MovingLanding_node.cpp you can see that most lines are simple assignment except on line 91 where the landing speed also has a minus sign in front of it. Whereas before this commit, the callback would be immediately called and the parameter would set a negative landing velocity, now the velocity stayed positive.

Here is the best explanation we can give for what happened at the DJI challenge. The quad approached the truck and as it saw the landing tag it started climbing in altitude due to the positive velocity. Once it got high enough that the AprilTag detection failed, it lowered down back to its flight_level_low altitude to search for the tag. Rinse and repeat, this was the oscillation we saw instead of the landing.

As for the “air break dancing” we saw where the quad didn’t seem to come back to the truck remains to be explained. My best theory is that somewhere along the way, DJI’s data transparent transmission which we used to send IMU and GPS data failed or became intermittent while the quad was far away (lowering the quad’s flight altitude seemed to have helped with this). As the connection cut off and came back while the truck drove away in a loop, some buffered GPS positions were sent to the quad. As both the current and older positions were sent back, the quad would constantly switch between trying to fly to the current position and flying to a position somewhere on the track. If this is the correct explanation, then proper data time stamping and clock synchronization would have taken care of this.

In summary, we lost 100 000$ because of a minus sign.

But why though?

You might be wondering why did we even bother having a minus somewhere in the first place?

If you’re familiar with aerospace navigation you’ll know that the usual reference frame for navigation is North-East-Down (NED) i.e. positive Z is towards the ground. In robotics systems such as ROS the coordinate frame is East-North-Up (ENU) i.e. positive Z is up, something more intuitive to the layman. The developers at DJI decided to strike a compromise between the two and have their API in NED but with Z flipped. This causes some confusion because some users think they are defining a left-handed coordinate system but really as soon as they receive a command, they flip Z and perform all their computations in NED, a right-handed coordinate system, as it should be.

So suppose you are like us and you have a non-trivial system that has to compute rotations and translations and such, you’ll do them in the NED system and then flip Z right before sending it to the DJI API. For consistency’s sake, you’ll have your entire system in NED and just flip it at the right moment. That’s why we see in the launch file that the landing velocity is positive, because positive in NED means downwards. Unfortunately the mistake here is to have flipped the sign too early in the configuration callback instead of right before sending the velocity command to the quad.

A costly mistake.

Cascading human errors

As I look over the entire challenge, it is clear that this failure wasn’t only due to the minus sign. For example, suppose practice day had gone our way, we would have caught this bug on practice day after a successful survivor search. But practice day would only have succeeded if we hadn’t had so much confusion about wifi. Somewhere along the way, we were also the only team so concerned by having wireless connectivity. Not only for IMU and GPS data for the landing but also to send back survivor detection data. I suspect that many teams didn’t even bother with the app because DJI didn’t even broadcast the Chromecast feed which was a mandatory feature for the mobile app.

Furthermore, we did detect this failure scenario the night before the competition but we dismissed it by saying the DJI simulator wasn’t behaving right. Why would we say that? A combination of being too tired to invest more energy in debugging things with a lack of trust in DJI’s tools after some of the headaches they caused.

There are many more “what if”s, “should’ve”, “could’ve” and “would’ve”s. I should have stayed at the hangar that day and encouraged more testing from the team while we waited our turn. I should have insisted when I saw the quad gain in altitude in the simulation the day before the flights. I should have made the team drop the search and rescue operation, especially after seeing that no other team had a good landing after the end of round 3 and knowing that it would eventually come down to a race to the fastest landing. I should have implemented a mandatory code review policy where someone had to at lest glance at your code before merging to master.

Lessons learned

The are quite a few lessons we can take away from this whole experience. But it’s taken me a while to really grasp what I should learn from the DJI Challenge.

1. Don’t over estimate your opponents

I used to think that it was impossible or that it couldn’t be harmful to overestimate your opponents. The worst case scenario is that you win by a larger margin if you put in maximum effort. In our case however, at the end of round 3 we were so convinced that all the other teams would be able to perform a full mission including a moving landing, despite no clear evidence for it, that we didn’t even consider dropping everything and focusing all our efforts on the landing. Had we not over estimated our opponents, we might have better allocated our efforts in the weeks leading up to the competition.

2. Code review even the mundane things

Yeah it feels slow and tedious. But there is a huge safety margin to gain from, at the very least, having someone else take a quick look at what you are doing. Even small or aesthetic refactoring can hide a 100 000$ bug.

3. Get some sleep

As the weeks progressed on, I could definitely feel the diminishing returns effect. I could spend more hours at the office while accomplishing much less. I was overworked but I didn’t want to admit it and things felt too urgent for me to give fewer hours. Giving a consistent 12 hours a day every day for weeks is a sure way of destroying your productivity. Especially when doing work requiring a certain amount creativity with complex logical thinking mixed in. Programming while tired is a sure way of introducing bugs into your code.

4. Make sure to set the expectations at the start

When starting a project, make sure everyone involved states what they are ready to give and how much they care for the project. It’s fine to say that you care little and you only have 1 hour to give a week. But at least then, the team can assign you things that are only worth 1 hour per week.

5. Enforce code freeze procedures

As much as it might pain some people to get their code frozen when they know that they can add one more feature or clean up one more thing. The only code that will for sure work is the one that has been tested. Not the one that was modified after a test. As the team manager, I should have forced a code freeze immediately after the successful test before leaving Montreal. Even if your code ends up missing a feature and no matter how much the team argues that they can do better, testing new code in production (competition) is never a good idea.

In the weeks leading up to the competition we did have a small discussion about code freezing but the answer I got was simply “never, there’s too many things to do”. Lesson learned, no code freeze is simply not an option when the stakes are high.