Already know about IARC and just want to know why I think it hasn’t been solved yet? Skip ahead.

I have some pretty strong opinions on how to tackle mission 7 of IARC and seeing how the competition still hasn’t been won 4 years later I figured it would be time to outline all of my thoughts on the subject through a series of blog posts. In this post, I’ll give a quick run down of what IARC is and what has been accomplished by teams until now. A caveat to this is that it’s very difficult to get information from the Asia side of the competition so all the information in this post is given from a North American point of view.

What is the International Aerial Robotics Competition?

To keep things short, I’ll just copy-paste the introduction from the official rules:

The primary purpose of the International Aerial Robotics Competition (IARC) has beento “move the state-of-the-art in aerial robotics forward” through the creation of significant and useful mission challenges that are ‘impossible’ at the time they are proposed, with the idea that when the aerial robotic behaviors called for in the mission are eventually demonstrated, the technology will have been advanced for the benefit of the world.

As such, the International Aerial Robotics Competition has not been a “spectator sport”, but rather a “technology sport.” Since its inception, over twenty two years has passed with six successful missions having been accomplished. Each time a mission was accomplished, some aspect of the state-of-the-art in aerial robotics was advanced beyond that which had previously been demonstrated.

The quick rundown of previous missions is as follows:

- Mission 1 (1990 - 1995): Carry a metal disc over a fence

- Mission 2 (1996 - 1997): Localization and identification of toxic waste barrels

- Mission 3 (1998 - 2000): Search and Rescue operation in a dangerous environments

- Mission 4 (2001 - 2008): Long range flight and secondary robot insertion into a building

- Mission 5 (2009): Locating a target inside a building

- Mission 6 (2010 - 2013): Retrieving a USB key from a building while avoidance security measures

In the past, every year a mission went unsolved, the prize money increased by 10 000 USD.

What is mission 7?

This mission is probably the least “useful” of the missions but still requires new technologies to be developed which can be applied to a variety of “real” scenarios.

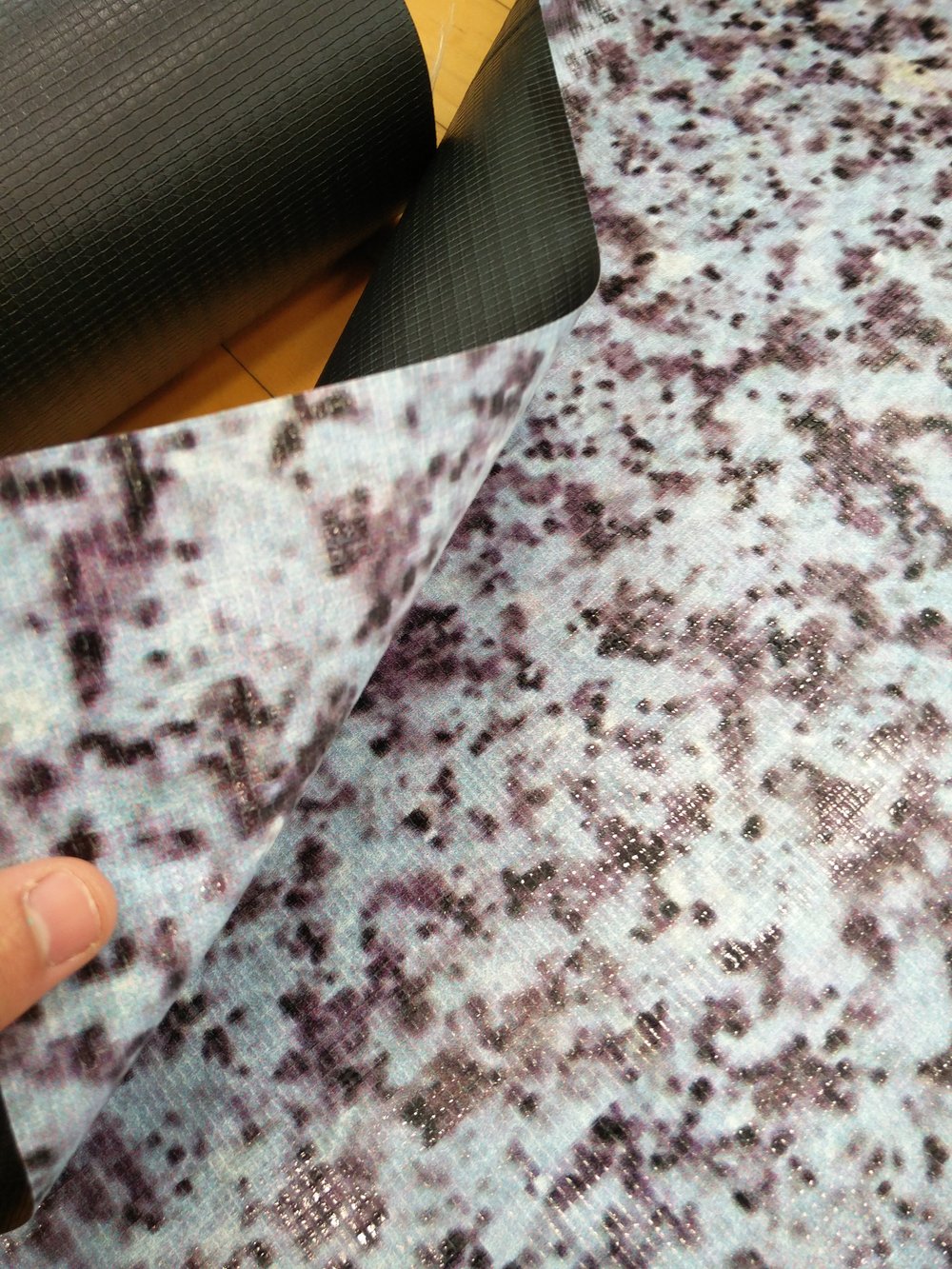

Mission 7 basically comes down to a sheep and shepherd game where ground robots must be herded by a Micro Aerial Vehicle (MAV) to a specific side of an arena. In addition, obstacle avoidance must also be demonstrated as robots with PVC cylinders roam the arena. As always, the aerial vehicle must be fully autonomous and new to this mission, it must not rely on any kind of external positioning system. MAVs interact with the robots by either tapping their top to make the turn 45° or blocking their trajectory to make them turn 180°. The whole thing happens in an arena made up of a grid of white lines over an “unknown optical surface” which was later standardized into a blue-ish stone like pattern.

Since the competition organizers predicted it would take about 3 years for the challenge to be solved, they immediately set the prize money to 30 000 USD.

The full mission rules can be found on the official website.

What happened in 2014-2015

I’ll try to keep this short I promise.

2014

Around November 2013 my school approved of my project to start an aerial robotics club to compete at IARC. It had been something I wanted to start since a bit before summer of 2013. I believe I had had the idea while I was actually on the road with the Esteban solar car team, I can’t remember what video it was but I saw a quadcopter fly on youtube and I was looking to start a project that could have more computer and software engineering students involved.

At the time, there was already a UAV club named SmartBird competing in the Unmanned Systems Canada Student competition. The person responsible for the student clubs had made it clear to me that my project would be refused if it was too similar to SmartBird. To emphasize the difference between the two clubs (in addition to us being rotary wing and them being fixed wing) we decided to sign up for IARC 2014 and compete in GPS denied aerial robotics.

Since the competition rules heavily hint at using optical flow for navigation we built a system around the only open source optical flow system that existed at the time: the px4 flight stack combined with the px4flow module. Our intention was simply to show up and IARC to learn from other teams and at the very least, not arrive empty handed with a good faith effort put into having something to demonstrate. Oddly enough, it turned out we were the only team capable of fully autonomous flight and the only thing we demonstrated was taking off, moving forward to the middle of the arena (by accident) and landing. This meant we (accidentally) placed first place in North America. During the flights, I had overheard one of the judges saying that it seemed like the teams had regressed.

There are a few things to unpack here. Summer of 2014, px4 didn’t have a gazebo simulation pipeline, nor was mavros a mature package (it was just starting). Furthermore, the offboard control mode didn’t truly exist yet. We had reused the c_uart_interface_example and a pair of LairdTech RM024 radios for communication. Since offboard setpoints didn’t exist, we had reused the set_quad_swarm_roll_pitch_yaw_thrust message to do offboard control. All in all, we had probably written less than 800 lines of code in our groundstation and a few in the px4 firmware. Most of our summer was rather spent tweaking the code, testing and dealing with hardware problems.

2015

2015 was a completely different story, we made a completely new quad from scratch and put in a lot more computing power. I had obsessed over the problem that optical flow was inadequate for the mission (more on that in some other post) and spent most of the year attempting to integrate visual odometry algorithms such as Semi-Direct Visual Odometry, Parallel Tracking and Mapping and Multi-Camera Parallel Tracking and Mapping. For a variety of reasons, including but not limited to my own incompetence in visual odometry, I wasn’t able to. Thankfully we still had optical flow for navigation and we were able to demonstrate tracking of a ground robot.

While we were demonstrating robot following, other teams were either showing up empty handed or with systems similar to us in 2014. Of note were Kennesaw State University taking off and landing in open loop fashion, Embry Riddle showing up again with a quad that doesn’t take off and University of Michigan drifting out of the arena.

What’s happened since then (2016-2017)

2016

My understanding is that not much has changed. In fact, my own team has regressed and in 2016 Elikos showed up with less than 2015. However, not many teams were able to demonstrate autonomous flight except for KSU and Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). In the end Elikos still managed to win on points and ended up first for a third year in a row. It seemed however that the competition organizers were annoyed that after 3 years the competition hadn’t been solved. Michelson and al. decided to publish a ranking in terms of aptitude to actually complete the mission rather than points, to stress the importance that until you can finish the mission, points don’t matter.

2017

2017 was again similar to the previous years. However, this time there were many teams present. New teams were able to demonstrate what we had demonstrated in 2014, basically taking off and landing somewhere in the arena. Unfortunately team Elikos took off and drifted out of the arena and team Ascend NTNU decided to fly manually to gather data. Of note is the new team Pittsburg Robotics and Automation Society with an impressive system almost built from scratch. If they are able to keep the pace of their development they would probably be in the top 3 North America teams most suitable to win.

Why hasn’t this competition been solved yet?

Although the technological aspect itself comprises many popular and ongoing research subjects such as visual odometry, obstacle avoidance and control theory for MAVs, the competition has yet to be seriously tackled by serious research labs except by Hong Kong University of Science and Technolgy’s UAV lab and Universidad Polytecnica de Madrid’s Vision4UAV lab. Most of the teams seem to be comprised of undergradute students doing their best to learn about a difficult subject and heavily relying on open source projects to tackle the basic challenges of this mission.

I believe the reasons to be threefold:

1. The prize money is too little

If you look at the 2017 Mohammed Bin Zayed International Robotics Challenge, world class research labs showed up to compete including Carnegie Mellon, ETH Zuric, Georgia Tech, University of Bonn, University of Zurich, Virginia Tech, Imperial College London, Beihang University and many more. In total about 316 teams had signed up with 25 being selected for finals. As a whole MBZIRC 2017 was similar to IARC Mission 7 in that it involved visually landing on a moving target(s) using MAV’s. Furthermore, the challenges are novel enough that someone working on them could possibly end up with a paper to publish even if they don’t place in first place.

The key difference here is that MBZIRC had 5 million USD in prizes to distribute to the winning teams. Compare that to 30K USD, which would be alotted to a single team, the difference is night and day. Keep in mind that my own team required an initial budget of about 15k USD just to get started in the first year. That’s 15k including about 4k in logistics spending to get the team from Montreal to Atlanta, the rest was to buy all the equipment needed for a team starting from scratch. So suppose we had won after 2 or 3 years, we would only have managed to break even.

When top researchers don’t show up, what’s left? A large group of keen undergrads with little resources but a love for the technology, trying to understand subjects just out of their reach.

2. The competition is difficult to market

When doing media appearances or interviews the first question is usually: What is the IARC? The problem is you can’t answer the question in only one or two sentences and have the interviewer completely understand, not only the challenge itself but also what the entire point is. In what real life scenario does a MAV have to herd roomba robots? Why is GPS denied navigation important? How does the roomba interaction work? How are you doing your localization? What are the practical applications of what you are developping? etc… Further more, the organizers don’t publish global team rankings. So even when we finished first, we had difficulty marketing that fact since we didn’t know our own standing vs the chinese arena. It is frustrating to have to explain year after year that nobody actually won the competition.

The difficulty in marketing the competition directly translates to difficulty in getting sponsors to fund the project.

3. The very nature of multi-year self-funded projects is problematic

Lets take for example Polytechnique Montreal’s 4 year engineering program. In the first year, most undergrads can’t do anything too complicated, we just learned how to program and our biggest project probably involves some kind of small procedural programming project to be completed with a team of about 4 people. Lots of hand holding is required here.

By the second year, electrical engineers will have finished with their theoretical control theory classes and most students should be apt to tackle broader programming projects. The only thing usually lacking here is self confidence and possibly to see the greater picture in terms of systems integration across various projects and engineering disciplines. Lack of self confidence often leads to students simply giving up instead of actually going through online ressources to understand a subject. In fact, some students never really grow out of the mentality of needing someone else to show them the way and teach them what they need to know.

By the third year you’ll have learned most of what’s important for you to be a junior engineer in a company in your discipline (if you hadn’t already). You’re probably at the head of the team or at least a senior and now you’re the one holding the first year’s hand.

By your fourth year you’ll (usually) be graduating at the end of the winter semester and if you’re stubborn enough to have stuck around all these years you’re pretty much doing what you were doing in your third year but you also realize the need to ensure team continuity and project sustainability.

Of course, this scenario is only one out of many but it serves to illustrate how difficult it is for students to really be dedicated to this competition. In essence, you only really have 1 year of full productivity and that’s if you stayed the whole time, which is the exception rather than the norm. At that peak in productivity, you’re still far off from the time commitments and the knowledge required to tackle this “impossible” mission.

Additionally all of this happens while you have to juggle funding the project by getting sponsors, managing the project, managing to pass all of your classes and (if you have one) managing life in general.

All of this amounts to a project that probably resets every two to three years, meaning undergraduate teams don’t have a good chance at solving the competition until open source projects are made available to tackle the more difficult parts of the challenge.