Looking back on that master’s degree

On December 21st 2017 I defended my Master’s thesis in front of a jury composed of Liam Paull, newly arrived at University of Montreal at the time, Richard Gourdeau and my thesis advisors David Saussié and Jérôme Le Ny. I was stressed out of my mind and had practiced the presentation every day during the two weeks leading up to it.

Great talk by Andre Phu-Van Nguyen today for his successful MS thesis defense. Congrats Andre and thanks for the great work in the lab these last two years! pic.twitter.com/CMn48jLaLd

— Jerome Le Ny (@jleny) December 22, 2017

The entirety of my graduate studies, starting in 2015, had been a rocky road and I was close to quitting more than once. I was way out of my element, with almost all of my classes requiring mathematical rigor I had not properly developed during my undergraduate degree in Computer Engineering. To say that things weren’t going well both personally and academically would be an understatement. My girlfriend at the time had broken up with me (explosively at that), I had failed a class, which automatically disqualified me from my graduate program and I my real research project still hadn’t started which meant I was more than a year into the program without being paid.

I decided that it was best to just accept that I’m a software engineer who doesn’t have what it takes to become a roboticist. I gathered what was left of my courage and went to see my thesis advisor to announce my resignation; man of my word, I would quit only after finishing the implementation of a robot path planning project he had given me.

As I sat there trying to explain why I was quitting, he glances at his screen and gasps. Our grant request was accepted, my research project would be starting and I would be getting paid shortly. I was now contractually bound to this research project for which half the cost had been paid by a drone company.

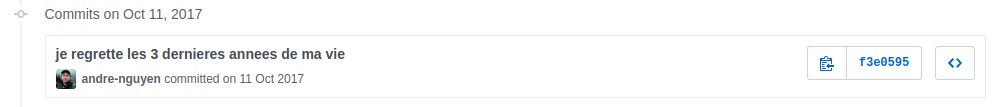

To be entirely honest, I had no idea what the legal consequences of quitting were, if any. I just knew I was committed to something and it would be in bad taste to break those commitments. I was barely hanging on but with the help of friends and my advisors, I kept pushing, put my name on those publications, passed the rest of my classes, delivered on that research project and wrote my thesis in about 2 months, judging from the commit logs.

Flashforward to December 22nd 2017, the jury awarded me my thesis with minor corrections, a huge weight was lifted off my shoulders. Never again, I thought to myself. I played video games all day for the first time in 9 years. I got bored.

A little break

I decided to pull the trigger on an idea I had had for a while to go on an extended trip in Asia. With about two weeks notice and a lot of googling, off I went. What was supposed to last about a month and a half got extended to almost three months. In that time I went through Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Indonesia and a bit of Australia. I was at a point where I was tired of the beach and I had topped out on how much more tan I could get.

I came back to Canada but I was still mentally fatigued and not quite ready to get a job. I must of spent the next two months doing nothing other than going to the gym or going out with friends as well as “studying” for a potential interview which would require solving programming questions. And by studying I mean I went through only two chapters of Cracking the Coding Interview.

First Job First Mistake

I remember I sent out a total of three resumes one to DJI for a senior roboticist position, one to Auterion and one to a local drone startup. I got through the three rounds of interviews with Auterion only to be told that it would be very difficult for them to hire internationally (?!). Clearly, I hadn’t put that much effort into finding my dream job. I was extremely picky about my opportunities, the drone world is rife with bullshit, people who don’t understand drones nor robotics.

I ended up accepting the job at the local drone company. The leadership was composed of engineers who understood drones, at least, more so that some unnamed startups out there. I was upfront about that aspect of what I was looking for in a job. “I don’t want to work for someone who doesn’t understand what I’m doing”. Clear as can be and it was clear to me that my interviewer did understand. I was then sold on the idea that I would be building a SLAM system for GPS denied navigation of drones. Right up my alley, all these engineering competitions and my thesis have prepared me for this. I start on my first day and I see a Gazebo simulation (not based on RotorS) of a quadrotor which integrates the autopilot firmware and some basic LIDAR sensors. Amazing. All these academic tools but now I’m paid to use them. It was explained to me that one of my main tasks would be to bring to life a SLAM system which was written in Matlab by a student doing a research project with the company. While this student was finishing his degree, he would also start working at the company to continue his research. Neat, I’ll be on the bleeding edge too.

And it all went downhill from there.

Things quickly devolved into me spending all my time teaching basic programming skills and C++ syntax someone could simply Google. When I suggested my colleague take a programming class or at least follow some online tutorials, he refused saying he was better at learning hands on. Fair enough. But when asked to do something he would simply reply, “I don’t know how to do that”. That’s kind of the point isn’t it? You figure it out by getting hands on and you learn.

While I had joined the company as a “Robotics Perception and SLAM Expert”, my role was diminished to being the programming assistant of someone with less hands-on, robotics, drones and software experience than I. Nonetheless, I stuck around thinking things would get better but eventually I started being more vocal about my complaints.

Bad Agile Methodology

While I had to teach programming I was also in charge of project planning, goal setting, building our sprints in Jira and to be entirely honest, I don’t think I’m qualified to be an Agile Coach. What little I know about Agile is the brief overview they give in school and the various blog posts you find online. However, reading through some parts of the Agile Manifesto, I couldn’t help but think this had nothing to do with us.

“Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software.”

We didn’t even have a customer, market research, nor did we even know what customers we were targeting. I would spend enormous amounts of time planning things in Jira instead of simply going ahead and writing software. More often than not, the time estimates I would enter would almost be bogus, especially with anything related to pure research. Should I really time box my literature review and stop it after only two days? How do you know there isn’t four days worth of literature out there for the system I am trying to build? It seemed like we had managed to combine the worst of two worlds, a small company with low resources with the bureaucracy of a large company.

We would have a daily company wide scrum (around 10 people) where some employees would literally have full conversations trying to problem solve instead of sticking to the basics. After a while I noticed that no one was actually listening when anyone from the SLAM team spoke. Sometimes my colleague would say something surprising and no one would react. I came to the conclusion that the entire company didn’t even understand SLAM or anything related to robotics for that matter.

There came a time when I simply asked what the project requirements are and the CEO bounced the question back at me. It was management’s way of acting like they trusted you with the technological decision but once you made the decision you would invariably be overridden. So much for the “freedom” and “responsibility” that comes with working in a small company. I replied with another question: Who’s the product owner and who’s the product manager here? I asked the question, not because I didn’t want to set the requirements, but because the previous times I had tried, I would either waste time arguing with my colleague about who was right when he hadn’t even bothered researching our competition or my decision would be overridden.

My question was met with silence on the Slack channel. It turns out management had an emergency meeting to clarify what everyone’s role was.

“Let’s forget Agile methodology roles because not everyone is familiar with them.”

My blood was boiling. They created a new organizational chart showing everyone’s role. Somehow a two person project had 7 stakeholders. The CEO would represent client interests, the COO would make sure we filled our sprints and followed agile-ish methods. The CTO would make the final calls on the technological decisions. The day to day scrums would be supervised by a “senior” software developer who had no background in robotics. I would be both a SLAM developer and a system integrator because I had a lot of hands on experience on robotics. My colleague would be a SLAM developer, in essence bringing his master’s thesis to real life.

Thus, the only management person who could understand what we were doing (the CTO) would only have a distant role in the project. Great.

Getting Your Ideas Shutdown

As mentioned previously, when I joined the company they had started building a drone simulator in Gazebo with some lidars. The drone ran a stripped down version of the autopilot firmware in a software-in-the-loop fashion. It wasn’t quite complete as the model wasn’t actuated by the firmware, but the state estimation was running using the simulated input which was good enough. Now one of the questions that came up was, what the end goal of the project was. The decision was taken to use lidar to also create 3D models of the environment, thus the product would then be both for GPS denied state estimation and surveying In fact, shortly thereafter, it was was decided that the product would be entirely separated from the company’s main product, a drone autopilot, but we were sill targetting a drone mounted payload.

Now something didn’t quite add up for me. To be able to do proper lidar based SLAM with the method being developped, it would require use to have the sensor placed horizontally. This would allow us to get the most scene coverage and thus, the best chance at proper point cloud alignment. The problem however is that there would eventually be places in the map left unscanned (parts of the ceiling for example) because it would be difficult given a quadrotor’s dynamics to point the sensor every where you need to create complete scene models. Traditional aerial scanners work in a pushbroom manner where a 2D lidar facing downwards is flown over an area with possibly overlapping passes for surface coverage. In an indoor scenario, this wouldn’t be possible.

As of writing, to the best of my knowledge there are two main companies focused on lidar based GPS denied navigation for micro-aerial vehicles with model reconstruction: Exyn founded by renown University of Pennsylvania professor Vijay Kumar and Emesent, a spinoff of Australia’s CSIRO, both of whom decided to adress the problem by mounting the lidar on an actuator to make it spin continuously. Other players include GeoSLAM, who’s beginnings trace back to technology licensed from CSIRO, developping mainly handheld scanners (also rotating) and Inkonova which also claims to be using a rotating 3D lidar but information is sparse on their product.

At the time I was still pseudo-in charge of project planning and I decided that down the line we would start working on a spinning lidar. I was immediately shut down by the CEO and told to replan the next 9 months. Making the lidar spin was a stupid idea and we had never planned this. I can’t say exactly what I was told after but it wasn’t pretty. A colleague of mine mentioned that our CEO only acts that way when he’s mad but really our CTO gets away with not planning things all the time, hence there was no need for me to actually replan anything. He was right.

I was concerned that no one had a better idea to tackle sensor coverage and if we ever decided to make our lidar spin, our algorithm wouldn’t be able to cope with the dynamics, making us waste another year redevelopping everything from scratch. I continued to voice my opinion and the responses were still mostly dismissal. “We’ll cross that bridge when we get there.”, “Maybe we can make it spin later and create a new SLAM algorithm when we do.” or my favorite response from my fellow SLAM teammate “We can put two Velodyne pucks on a drone, one to do the state estimation and one to do scanning in a pushbroom fashion.”

Cue Geralt saying “fuck”.

The one guy who can do the SLAM math doesn’t know anything about drones and wants to add 1.2kg of lasers to an indoor drone in addition to the wiring, mounting hardware and onboard computer.

A few weeks later, the CTO would go to a mining conference in Montreal where he got to see both Exyn and Emesent. He came back saying that making a 3D lidar spin made sense and we should look into it. At that point I just felt insulted. Not only was it a lie that I could have a role to play in the decision making, my ideas were only of value if they were the same as the ones from someone in management.

Head In the Sand

When I joined, I found it puzzling that I was the only employee with an academic background in robotics but I didn’t think much of it. After all, robotics is a multidisciplinary field that requires a great deal of collaboration, but when your team is small, I believe its important for people to be multidisciplinary and apt at understanding as many facets of the project as possible. When working in a small startup, you simply don’t have the ressources to hire all the experts you need. Instead, you’ll need to wear many hats and help out wherever you can to advance the project.

The company managers seemed to have the exact opposite mentality to me. Our COO explained that “a math guy should do maths and a programming guy should program.” Thus all employees become very narrow experts and pass eachother the ball when needed. The problem here was that we simply did not have the ressources to move forward. There came a time when we needed to build hardware to synchronize our lidar with our other sensors. Our hardware/embedded guys were busy for the forseeable month with some features in another product and wouldn’t be able to provide their expertise. On one hand, I could’ve feigned incompetence like everyone else and simply said that it wasn’t part of my job description as I am a Robotic Perception and SLAM expert. On the other hand, I do have a sense of responsibility and decided to go ahead and learn how to use CubeMX to do a little bit of embedded programming.

Anytime my teammate didn’t want to do something he would simply repeat the same thing: “I don’t know how to do that.” Never followed up by “But I’ll look into it.” or “I’ll try to figure it out.” I would end up having to either show him how to do it, by doing it in front of him, or doing it on my own. It seemed generally accepted that if things we’re even slightly outside of your comfort zone it was ok to pass it off to someone else. Which is how I ended up spending weeks of my time there working on continuous integration, docker containers, server maintenance and writing infrastructure code for my colleague instead of actually working on SLAM algorithms as was in my job description. In essence, I had become a Devops/Personnal Programming Assistant to a guy with less knowledge and less experience than I.

The lack of responsiblity in the company was so bad that one guy would act like he never heard the company phone ring even though he sat right next to it. I would have to get up and walk two desks over to answer for him.

A Robotics Company With No Roboticists

On the subject of no one in the company having a robotics background, things couldn’t have been worse. After being kicked out of being a fake-project manager and having our CTO take over all technological decisions, it was apparent that the CTO didn’t even have time to follow up on the project. Thus, the project supervisor remained the COO and it would be his decision what the team would prioritize. Cue the most frustrating quote of all time:

Knowing the direction of gravity doesn’t matter, we just want lidar scans.

— COO of the company

I tried arguing that things would drift and eventually the ground wouldn’t be flat but I was ignored. Later on, when new maps were produced you could see parts of a building caving in on themselves because of a drift in roll and pitch angle.

My frustrations with the lack of robotics knowledge wasn’t limited to the COO. The SLAM team’s day-to-day operations (morning scrum) was supervised by a software guy with a great disdain for anything robotics related. On one hand he would vigorously argue about code line lengths and architecture while simultaneously denigrating anything not related to software engineering. In fact, he seemed to have a hard time saying the word “voxel” without also appending the suffix -shit.

Yeah just do your voxel-shit or whatever and we’ll take over from there.

There’s something deeply irritating when someone disrespects your core comptency, but the whole thing because a huge joke when you remind yourself that you would in an “aerial robotics” company with no roboticists.

Moving on

I could go on and on with the problems I faced but I’m already tired of writing this post. To summarize in point form:

- My ideas would repeatedly be shutdown only to be brought back when someone in management decided it was a good idea after seeing a competitor with the same concept. No one would bother actively researching the competition.

- My CEO wasn’t developping a business case. All he had going was this one guy from a construction company saying he would be interested in such a product. I later realized we weren’t actually there to develop a product but to fill a series of contracts the company had with the Government of Canada. I don’t think I can say what we did, but I do think I can say that I wasn’t proud. Nothing illegal of course, but I do think my research advisors would have been very much dissapointed.

- The project was poorly managed, there was no clear vision on what we were building. There weren’t even any specifications or requirements to meet and yet we were following tight pseudo-agile methodology with deadlines and 3-9 month schedules.

- I was stuck doing a mix of embedded programming and hardware to synchronize sensors, continuous integration because apparently 2/3 of the software guys in the company couldn’t be bothered to maintain our Jenkins server, teaching C++ to my teammate and writing some infrastructure code to accomodate his poorly written algorithms. Basically no robotics.

I was a bit over a year in and couldn’t take it anymore. All that time had been wasted and I had nothing to show for it. My career was off to a terrible start and I had learned nothing in that span of time other than the fact that I didn’t want to be surrounded by people who had less experience than I did. And thats saying quite a bit coming from someone fresh out of school. While others would relish at the chance to demonstrate their knowledge and show the way for the less experience, I wanted to be somewhere where I’d be the dumbest one there with everything to learn. I wanted to step on a springboard that could eventually launch me to a job at X.

I started looking for a job but this time I actually put some effort into it. After a few interviews with various companies, I decided on join the Applanix Autonomy team. While very small team and not quite related to drones, it looked like a great opportunity for learning and career growth without having to move to San Francisco with all the startups backed by VC money.

Today, I am cautiously optimistic about the move I made. The guys are competent, the business development managers understand the technology and are serious about making a business out of it. The product is already being deployed on customer premises with the team doing multiple field deployments a year. All new employees go through a sort of orientation on their first week which was my chance to ask some longstanding questions I had accumulated over the past year. I learned more in a two hour conversation with the guy working on qualifying IMUs than I did in an entire year at my previous company.

During a meeting with the Director of Engineering, I was explained the engineering process within the company, which was a bit of a mix between more rigid almost aerospace-like processes but with some of the flexibility from more modern software development practices such as Agile. To my surprise, and great pleasure, I was told “You have a right to ask what the specifications and requirements are.”

The thing I used to have to fight for was now my God given right.

Thank Fuck